First uses

Made famous through the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 the infantry square had actually been around since the Roman times. So not only since Wellingtons infantry square – as it was also commonly known – but so much longer.

Described by Plutarch, the Roman legions would use a large full infantry square at the Battle of Carrhae against Parthia’s large cavalry; this though must not be confused with the arrows and spears protection square’s of the testudo formation, usually these had the shields side to side on all fronts and also overhead. Han’s Empire’s mounted forces were very mobile units used with light cavalry allowing very mobile square to be formed, these were predominantly used in clashes with the mainly cavalry Xiongnu armies. During the siege of the mountain settlements of the Nomads, Han’s squares repelled lancer attacks.

It appears the square dropped off some what after the Roman’s and Han’s Empire’s. Though during the 14th century it did make a comeback as the schiltron and later the pike square – tercio.

Square formation

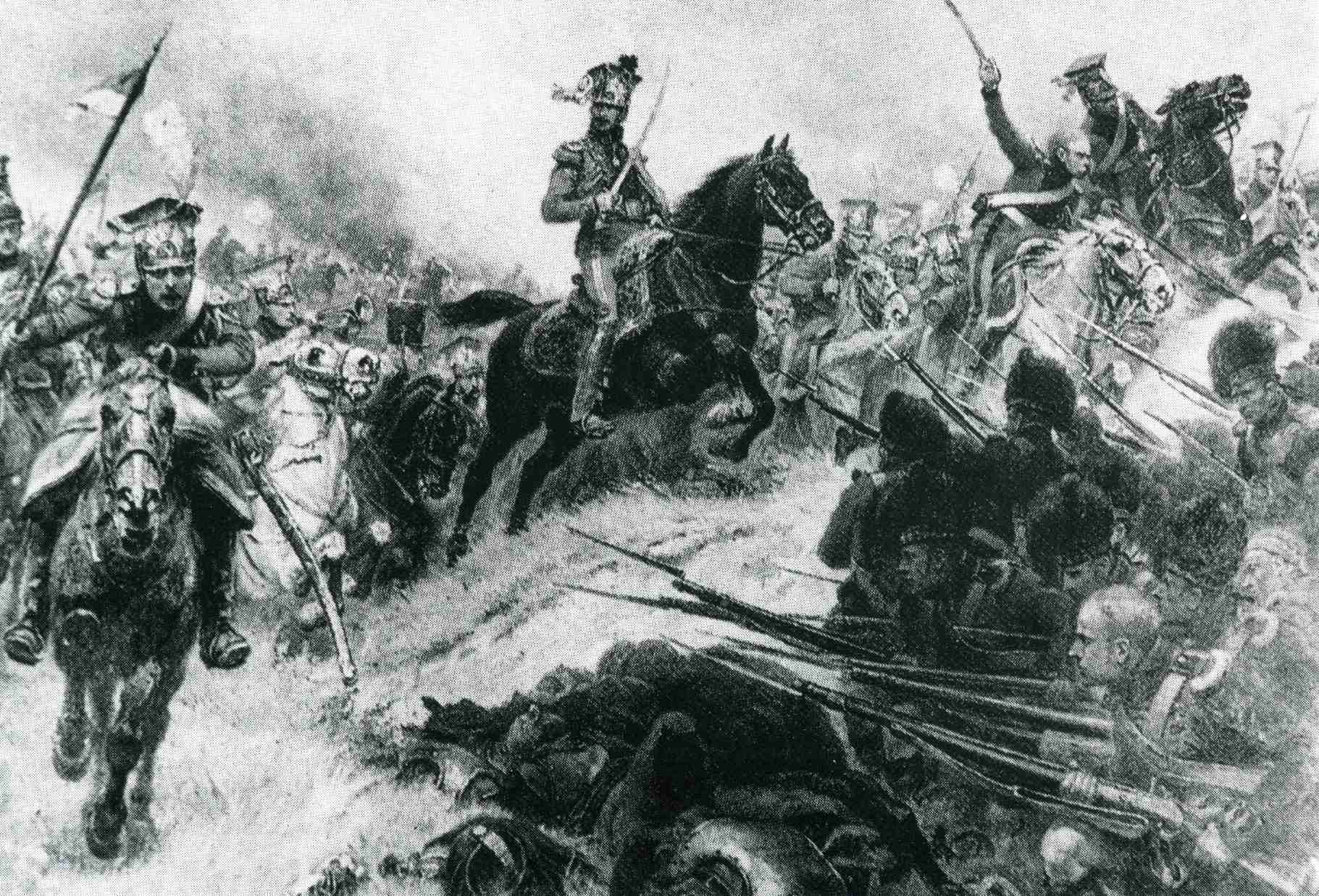

The main usage of the squares were the hollow formations during the Napoleonic wars, sometimes the formation could also be more rectangular. Each side would have a minimum of two ranks (usually four in the case of Wellingtons) of infantry with bayonets fixed on their single shot muskets. The first rank would be kneeling with the muskets shining bayonets pointing at an angle of around 45 degree. The second and/or third ranks would be stood with the bayonet fixed muskets to the shoulder taking aim and ready for the order to open fire in rank order. The third and/or forth ranks would be reloading the muskets for the ranks in front.

Such a square of this type would require around 500 soldiers, the officers with a reserve force would be positioned in the centre, the reserve force would be utilised to fill gaps that might appear in the squares, and these squares would also be very tightly packed shoulder to shoulder. The infantry would wait until an advancing cavalry was at a range of 30 metres and then the commanders would give the order to open fire, the idea was to try ensure the fallen cavalry caused problems with the cavalry behind, therefore slowing the advance and allowing the infantry to change muskets for the loaded one.

Such a square of this type would require around 500 soldiers, the officers with a reserve force would be positioned in the centre, the reserve force would be utilised to fill gaps that might appear in the squares, and these squares would also be very tightly packed shoulder to shoulder. The infantry would wait until an advancing cavalry was at a range of 30 metres and then the commanders would give the order to open fire, the idea was to try ensure the fallen cavalry caused problems with the cavalry behind, therefore slowing the advance and allowing the infantry to change muskets for the loaded one.

Single shots of an undisciplined rank would warrant ineffective, causing problems for the ranks behind helping to reload in order therefore allowing the advancing cavalry to get much closer, being able to use their pistols and even closer use their lancers. Opening fire too late would cause the stricken cavalry to fall heavily into the squares, this in itself made openings for cavalry to enter the square and break it up from within.

Squares were not an out and out static defence; good commanders could control some movement which could also trap cavalry, against the Ottomans at Mount Taborin 1799 the French managed just this. It was also vital that squares were staggered so they did not risk the chance of one square shooting at another.Wellington’s infantry squares at Waterloo with stood 11 cavalry charges.

To break a square

Squares stood up very well against cavalry charges in various battles, Jena-Auerstedt 1806, Pultusk 1806, Fuentes de Onoro 1811, the first Battle of Krasnoi 1812 and Lutzen 1813. The Rio Seco battle did though have a square broken receiving huge casualties. To break a square the cavalry would try to seek out a poorly organised side and entice the infantry to give some chase leaving gaps in the square. The corners of the square were the weakest points, cavalry would charge at these in close formation, false attacking fronts were also used to try and get the infantry to fire leaving them at the hands of the cavalry lancers, but well drilled squads need not have this problem.

Artillery was the main attempt to break a square, but would need to be brought closer to get direct hits on the compact infantry square, the use of fast responsive horse artillery with the attacking cavalry would get them within range. The attackers would cause the defenders to form a square and then the horse artillery could quickly position and open fire. If infantry could not form a square fast enough then the cavalry would inflict huge casualties, or destroy the whole units. Weather can play a part, rain storms which would cause the solders musket gunpowder to be useless. Rain was present at Waterloo but not during the French cavalry attacks on the squares.

Artillery was the main attempt to break a square, but would need to be brought closer to get direct hits on the compact infantry square, the use of fast responsive horse artillery with the attacking cavalry would get them within range. The attackers would cause the defenders to form a square and then the horse artillery could quickly position and open fire. If infantry could not form a square fast enough then the cavalry would inflict huge casualties, or destroy the whole units. Weather can play a part, rain storms which would cause the solders musket gunpowder to be useless. Rain was present at Waterloo but not during the French cavalry attacks on the squares.

Napoleonic wars

Napoleon was a magnificent leader, he pulled the French from the revolution and guided them to many victories in Europe, installing Franceas a major dominating country within Europe. He started to come unstuck when he invaded Russia and lost the majority of his Grande Armee. The sixth coalition forces defeated him, escaping from Elba he again took the leadership role of France but this time he was completely defeated at Waterloo.

Survival

The infantry square did survive through the 19th century but these were not of the type used during the Napoleonic wars, these were much larger and often surrounding tents, artillery, and horses, being more common during battles within the European colonial wars; Anglo-Persion war, Battle of Khushab, Zulu, Mahdist, Tamai, and Abu Klea. The last use of a square was in 1936 and the Battle of Shire during the Second Ital-Ethiopian war, Italians were advancing when a possible Ethiopian counter attack was mentioned, the counter attack never happened.

During this time period the square was pretty much a European affair, only one documented infantry square was used outside of the European forces, this was during the American civil war at the Battle of Rowletts Station. An attempt was made to form a square in South Americaduring the War of the Triple Alliance; this was towards the end of the Battle of Acosta Nu and the Brazilian cavalry destroyed it before it was complete.

The onslaught of modern warfare, technology, and decline in cavalry use put an end to ‘Wellingtons infantry square.’

Pingback: Ever wondered how the infantry square worked? | Stuart Briggs